Exterior of Preus Museum (Courtesy Preus Museum)

For those of us who got involved in collecting photography at a later stage, the 1960s and 70s when the modern photography market began to take shape seem like heady days indeed. There was an abundance of material, often regarded by the world at large as being worth no more than the paper it was printed on, chased by a small group of dedicated dealers, collectors, and then from 1971 onwards, by the two leading auction houses as well.

It's a history yet to be fully written though bits of it tend to pop up in introductions and essays in monographs and catalogues. Sam Wagstaff's involvement was described in more detail in Philip Gefter's biography "Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe", published in 2015. Alongside Wagstaff, the same names tend to reoccur, Harry Lunn, Rudi Kicken, Gérard Levy, Daniel Wolf, Philippe Garner, Stephen White, George Rinhart, and others, but I have rarely come across the Norwegian collector Leif Preus.

From his base in Norway he assembled a vast collection of photographs, cameras and other technical equipment, as well as books, letters and other ephemera. His collection would go on to form the basis of the Norwegian National Collection of Photography, housed in Preus Museum in Horten, where according to its director Ingrid Nilsson, "the archives are filled to the brim and storage is now a major issue for us".

The museum and its collections have a low profile internationally. The location probably doesn't help. "It's in the middle of nowhere" as a friend in Oslo told me, that nowhere being on the outskirts of Horten, a small town 90 kilometers outside of Oslo and then a good 15 minutes walk from the train station.

Preus originally kept the collection in his own private museum, founded in 1976, but sold it to the Norwegian state in 1995, on the condition that a new museum would be built in Horten, the town where he was born in 1928. Having served eight years in the Norwegian navy, he founded a profitable photography and film processing business in 1956, which eventually grew into a chain of shops and its own lab. The new museum, housed in a refurbished naval building, opened to the public in 2001.

There are few hints of the treasures that the museum holds on its website. This is largely because of budget restraints. Director Nilsson tells me, "A vast proportion of the photographs are still under copyright and it would cost a fortune to create an online museum, funds that we simply don't have."

I first heard of Leif Preus some twenty years ago when Tore Holter, the then editor of the Norwegian magazine Fotografi and himself a collector, told me about the Preus collection. Its vast holdings include work by Edward Steichen, including some of his paintings, Lewis Hine, the Czech Avant Garde, Fox Talbot, and much more besides.

"The dealers used to travel to Horten to sell to him, people like Harry Lunn, Rudi Kicken and Stephen White," Holter told me.

I caught up with Stephen White, who was a close friend of Leif Preus'.

Panorama of exhibit space of Preus Museum (Courtesy Preus Museum)

"I probably knew Leif Preus better than anyone in the photography field. I heard about Leif in 1977 when I first started out as a dealer and put together my first catalogue. A friend of mine suggested I send Leif a catalogue and as a result he bought a few prints from me. I started going to Europe in the 70s, two or three times a year, buying from the auctions, whenever I could that is, because I was on a very thin budget. I did a kind of circle, traveling to cities to see just one specific person, as collectors were so hard to find back then. I went to Amsterdam to see Bert Hartkamp, to Hamburg to see F.C. Gundlach, and I would fly to Oslo, hire a car and drive to Horten to see Leif and usually stay overnight. I knew that if I went there he would buy for at least $5,000 worth of photographs, and that was a fair deal of money back then. So it was a guaranteed sale and I liked him and loved what he was doing with the museum, relatively small and private."

And dealers had to travel to Preus. White explains, "He had a big business to run. He went to London occasionally but generally he didn't attend the auctions. The main reason was that Leif didn't fly. During WWII he was in a plane and it terrified him. He thought it would never land. He promised himself that he would never fly again. And he didn't. He was that kind of person. Very strong willed and a fine human being."

Eventually, in 1984, Preus came to Los Angeles to see White. "It was a complicated journey. He and his wife drove to Gothenburg in Sweden, took their car on a ferry to Newcastle, drove to Southampton, then sailed to New York and took a train to Los Angeles to visit me. They stayed for a week and we had a great time. At that point I hadn't offered him anything for a while. Two years earlier, he had gotten into a fight with the Norwegian tax people, this because of the museum in Horten. It was part of his business and as such, he should have been able to deduct the costs and expenses for running the museum, and they fought him on that. So he stopped collecting. This didn't bother me, and we remained friends. I knew what the situation was so I didn't offer him anything."

White had himself gone through a tough time. "It was the end of a horrible recession. Instead of having a gallery, I now had a small space in an office building in Beverly Hills, open by appointment. I didn't expect to sell anything to him, but he told me that he had settled the tax matter with the government and that he was going to start collecting again. He bought $125,000 worth of photographs, which got me out of a real hole. I was in debt up to my teeth at that point. I opened the drawers, and Leif just kept piling them up. I couldn't believe it!"

So what did he buy? "He bought a lot of Steichen photographs, one of his favorite photographers; and among the first things I ever sold to him were three painting by Steichen. He liked Stieglitz and the photo-secession--all the classical names. But if he liked a photograph, and that's where he and I really shared a common passion, he bought it and didn't care who had made it. So he built a collection that was mainly classical 20th-century photography but he had a lot of 19th-century material as well. I remember some early German salt prints that I would have died for, they were so wonderful. He had gotten them from some camera dealer in Germany, who had sold them to him for nothing."

White points out that despite the vast collection of prints, Preus' main focus was cameras. "He was a real camera guy. He started with cameras and expanded into photographs, and the museum had plenty of both. He had a lot contacts, and people knew about him--certainly the camera people, but he wasn't that well known among the photo dealers. And as I said, you had go to Horten to see him. And not that many people were willing to do that."

Was he competitive with other collectors? "The camera people all knew him. With regards to photo dealers, I don't think he interacted enough with them or with the other collectors who were around at the time for competition to arise with people like Wagstaff, who would glare at whoever dared to bid against him at the auctions. Wagstaff and Paul Walther would simply keep their hands up at the auctions, 'I'm going to buy this and screw you!' That was their attitude. Leif wasn't part of that and only went to the auctions on rare occasions. Plus, there were so few people in the market back then that there was enough good material for everybody."

White continues, "I did a show in 1989, "Parallels & Contrasts", with photographs from my collection. After New Orleans, it travelled to three museums in Europe, including Glyptoteket in Copenhagen, and Leif and his wife drove down to see it. I stayed in touch with him, but after he sold his collection to the Norwegian government I think he kind of lost interest since it wasn't his any more. It was also my impression that they shut him out in a way. They hired their own curator etc., and he was disappointed in the way they dealt with it. But we were in touch until shortly before his death in 2013."

Speaking to Norwegian friends, it is clear that Preus has left an enormous legacy in Norway, not just the museum and its collections, but in the way he enthused several generations of photographers and collectors and opened the general public's eyes to the medium.

White says, "That was one of the reasons he was willing to sell the collection to the government. He felt it would give people the opportunity to see and learn about the history of photography, and that was very important to him. It's interesting, so many of those early collections went to museums. Bert Hartkamp's went to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Wagstaff's to the Getty, and I sold mine to the Photographic Center of The Tokyo Fuji Art Museum in 1990, although I have built an even larger one since then. But those collections were the nuclei of what was available to museums. It meant that they didn't have to buy prints individually. But I think Leif could have negotiated a better building in Oslo. And the museum would receive more visitors there than in Horten."

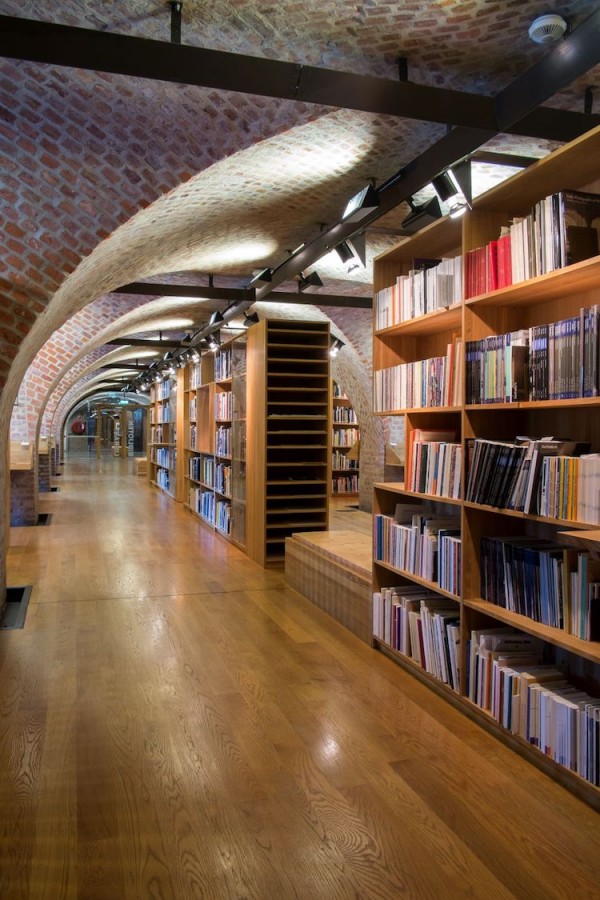

Library of Preus Museum (Courtesy Preus Museum)

A couple of days after my conversation with White, I spoke to Ingrid Nilsson, director of the Preus Museum since 2009. She told me about developments after Preus sold the collection.

"The Norwegian state purchased the collection in 1995 and during the years leading up to the opening of the new museum in 2001, a vast number of photographs were bought, mainly by leading international names, such as Irving Penn and Arnold Newman. Once opened, the museum's purchasing budget was severely slashed, and today it is around 100,000 Norwegian Kronor. So we tend to buy when we put on exhibitions, and we focus on gaps in the collection, such as Scandinavian fashion photography."

Other museums also have limited budgets and chase sponsors for purchases, but as Nilsson explains, "Our archival storage facilities are absolutely full and it wouldn't be right to seek outside sponsorships to buy prints that we couldn't store properly."

And storage is a major problem for the museum. In an interview published on the national broadcaster NRK's website on June 4, 2018, Nilsson vented her frustration with the Norwegian Ministry of Culture, that while the prints are kept under archival conditions, a vast portion of the technical equipment is stored in an attic without temperature and humidity control.

Nilsson explains, "I brought the problem to the ministry's attention immediately after I started here in 2009, but so far we haven't received the necessary funds to deal with the storage problem. And the collection doesn't belong to the museum. It belongs to the Norwegian state, and we can't care for it properly. Nevertheless, I expect the problem to be solved within a few years. The National Museum in Oslo will move into a new building next year and that means freeing up storage space in the old building. There's a also an organization called Foto Norge, and they're working hard to establish a house of photography in Oslo and that would make it possible to show temporary exhibitions based on our collection. At this point, there's no space to show large photography exhibitions in Oslo so it is very much needed.

Michael Diemar is a London-based collector and consultant. He is also editor-in-chief of The Classic, a new free magazine about classic photography. He is a long-time writer about the photography scene, writing extensively for several Scandinavian photography publications, as well as for the E-Photo Newsletter and I Photo Central.

Share This