London Auctions Were a Mixed Bag This Spring

Dave Heath, Poet-Photographer, Dies from Fall on His 85th Birthday

Membership in the Daguerreian Society and 19th-century Photography

French curator Clément Chéroux Takes over the Reins in San Francisco

Vintage Works Is Running Largest Sale Ever at Half Off

Photography Books: Josephson's Conceptualism, Sternberger's Pathognomicism, Katsiff's Nature Morte

New Website for the Art Institute of Chicago's Alfred Stieglitz Photography Collection

Photo News Briefs

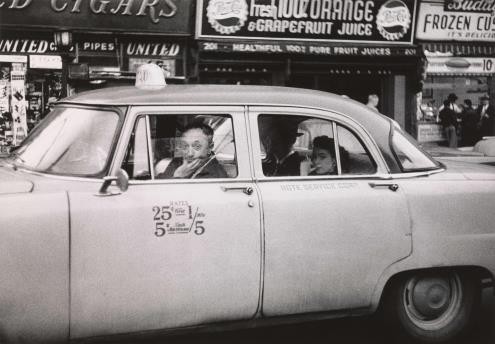

Diane Arbus (1923-1971). Taxi driver at the wheel with two passengers, N.Y.C. 1956 (© The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC. All Rights Reserved)

DIANE ARBUS: IN THE BEGINNING. Through November 27 at Met Breuer, 945 Madison Ave., New York, NY. Information: http://www.metmuseum.org/visit/met-breuer; 1-212-731-1675

This is very much another long, hot summer of Diane Arbus. The famed photographer, who was only 48 when she took her own life in 1971, has never been out of fashion in the art world. Her influence still simmers, darkly and disturbingly, and radiates through the work of the most potent and controversial photographers to come in her wake. If anything, she is more dominant than ever.

That's largely due to a major solo exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of New York's new Met Breuer gallery, which continues through November 27, along with a new and somewhat shockingly intimate biography by Arthur Lubow (Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer; Ecco). Such sharp focus on Arbus's life and art reminds us, freshly, how much we have been in thrall to her full-frontal portraiture of America's urban edge and its fringe-dwellers--the dwarves and giants, obese nudists, the housebound and the outcast from whom we perversely crave knowledge and distance.

The Met Breuer exhibit, brilliantly conceived by Met photography curator Jeff L. Rosenheim, is a tour-de-force presentation, with floor-to-ceiling columns across the second-floor gallery, repeating in layers, each column hung with a single photo on its front and back. This dreamlike isolation of imagery–isolating the isolated souls of Arbus's art–is powerful and, like dreams, somewhat random.

The 100 or so photos–from the Met collection given by Arbus's daughters--were shot between 1956 and 1962, her early years as an independent artist (and after she had left her husband, Allan Arbus, and their partnership as fashion photographers for Glamour magazine). A viewer can look at any of them in any order, because in those years Arbus was finding her style in an almost scattershot way: blurry street shots of inanimate trash alternated with purposeful shots of people staring into the lens from a city bus, for example, or–more emblematically–images of drag queens dressing in a backstage demimonde.

Rosenheim makes it clear for us that Arbus was picking up from the prevailing New York street photography of Lee Friedlander or Garry Winogrand, and especially Lisette Model, with whom Arbus studied. (Rosenheim includes a gallery with work by Arbus's predecessors and contemporaries, from a Walker Evans subway photo to an August Sander portrait.) But rather than indulge the almost clinical objectivity of the male gaze, Arbus followed up on Model's more subjective approach, to the point of establishing relationships (in some cases sexual) and developing long-term bonds of trust with her subjects.

Thus, the early images are a swirl of intentions–anonymous pedestrians, and some Friedlanderish store windows that don't scream Arbus. But once she gravitated toward the darker side, such as the freak shows of Hubert's Dime Museum in Times Square, with its physical oddities and tattooed icons, she began to seize on the strange fascinations pop culture was just beginning to mainstream. Just as importantly, she located the uncanny in the everyday–an old woman on the street, her eyes closed, or a young woman carrying her child urgently in Central Park.

Fittingly, as the '60s began, Arbus became, well…Arbus. Her 1960 shot of a swarthy man stripped down to his boxer shorts on a Coney Island beach, still semi-dressed in black socks and shoes, is classic and funny, because the man is so utterly New York that whether he is half-nude or not doesn't really transform him.

But by 1962, Arbus effected a transformation of her own by switching from the rectangularity of the 35-mm print to the square-format Rolleiflex, a true portrait camera offering greater detail. Such 1962 images as that of a child holding a toy hand grenade mark the onset of her mature style. They throw into sharp relief the formative qualities of the earlier work–of a boy staring into her lens as he steps from a curb, or of a schoolgirl stepping onto one–and begin to codify the narrative terrain staked out by her '50s images of drag queens or the tattooed "Jack Dracula."

Appropriately, Rosenheim concludes the exhibit with selections from Arbus's great portfolio, "A box of ten photographs." These iconic shots from the mid-'60s–Identical twins in Roselle, N.J., a young man in curlers at home in New York, the 8-foot-9 "Jewish giant" Eddie Carmel, or the Mexican dwarf Lauro Morales–make clear to us where the early work was leading and how it would pay off, in a new American Gothic.

Indeed, Arbus's vision would haunt us unflaggingly from that point on, finding expression in everything from the renewed appreciation of Todd Browning's film "Freaks" to Stanley Kubrick's ghostly twin girls in his film "The Shining," along with countless other fixations on the domestically weird and the poignantly marginalized. Arbus may have left us, tragically and prematurely, but she is far, far from gone.

Matt Damsker is an author and critic, who has written about photography and the arts for the Los Angeles Times, Hartford Courant, Philadelphia Bulletin, Rolling Stone magazine and other publications. His book, "Rock Voices", was published in 1981 by St. Martin's Press. His essay in the book, "Marcus Doyle: Night Vision" was published in the fall of 2005. He currently reviews books for U.S.A. Today.

(Book publishers, authors and photography galleries/dealers may send review copies to us at: I Photo Central, 258 Inverness Circle, Chalfont, PA 18914. We do not guarantee that we will review all books or catalogues that we receive. Books must be aimed at photography collecting, not how-to books for photographers.)

London Auctions Were a Mixed Bag This Spring

Dave Heath, Poet-Photographer, Dies from Fall on His 85th Birthday

Membership in the Daguerreian Society and 19th-century Photography

French curator Clément Chéroux Takes over the Reins in San Francisco

Vintage Works Is Running Largest Sale Ever at Half Off

Photography Books: Josephson's Conceptualism, Sternberger's Pathognomicism, Katsiff's Nature Morte

New Website for the Art Institute of Chicago's Alfred Stieglitz Photography Collection

Photo News Briefs

Share This