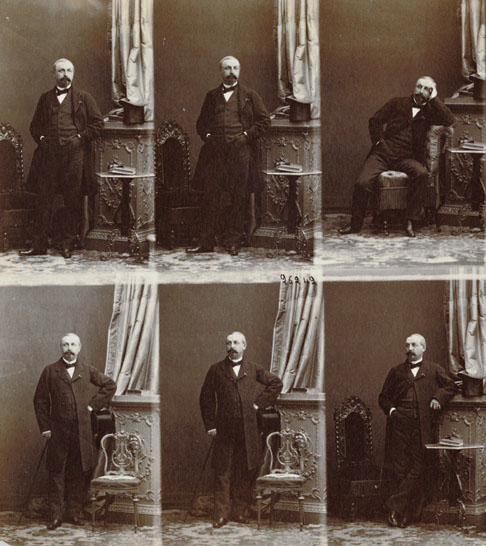

Langlois--Redoute Gervais

Although eventually victorious, the British and their French allies pursued the Crimean War (1854-56) with little skill, poor generalship and logistical incompetence. It was the only European war fought by the British between the ending of the Napoleonic conflict in 1815 and the opening of WWI in 1914.

The war escalated from a small quarrel between Russian Orthodox monks and French Catholics over who had precedence at the holy places in Jerusalem and Nazareth and, in particular, who had possession to the keys to the Church of the Nativity. Tsar Nicholas I of Russia demanded the right to protect the Christian shrines in the Holy Land and, to back up his claims, moved troops into Walachia and Moldavia (present day Romania), then part of the Ottoman Turkish Empire. In October 1853 Turkey took action by declaring war on Russia. The Russian fleet then destroyed the Turkish flotilla in the Black Sea.

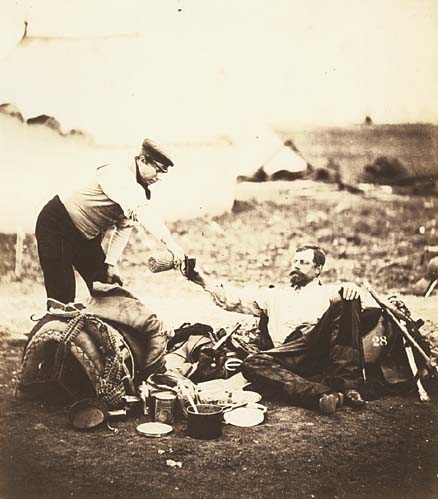

Cundall & Howlett--Heroes of the Crimean War

Russian domination of Constantinople and the Straits was a perennial nightmare of the British. With the two powers already deeply suspicious of each other's intentions in Afghanistan and Central Asia, the British couldn't accept such Russian moves against the Turks. Louis Napoleon III, emperor of France, eager to both emulate the military successes of his uncle Napoleon I and to court favor with militant clerical groups in France, allied himself with Britain. Both countries dispatched expeditionary forces to the Balkans.

The war began in March 1854 and by the end of the summer, the French and British forces had driven the Russians out of Walachia and Moldavia. By all rights, the fighting should have ended then, but the alliance decided that the Russian naval base at Sebastopol was still a threat to the region, and in September 14, 1854 the French and British, along with their Turkish allies, invaded the Crimean peninsula.

They landed in Calamita Bay, south of Eupatoria, and on September 19th the three armies marched south along the coast in the direction of Sebastopol, 30 miles away.

Sebastopol was virtually invulnerable to an attack from the sea and the land defenses were also formidable. The major strong points in the defenses, the Redan, the little Redan and the Malakoff bastion, would become notorious as places where loss of life was high indeed.

As the British and French prepared their siege works, the Russian army on the British right flank attacked. They were pushed back at the battle of Balaklava but only with great losses and the virtual annihilation of the British light cavalry. Another strike by the Russians resulted in the Battle of Inkerman, a murderous skirmish fought in a dense fog and heavy brush that limited visibility to a few yards. Again the Russians were neutralized.

The war settled down to one of trench warfare and artillery as the Allies pushed their trenches nearer the defensive lines of Sebastopol. The winter of 1854-55 brought great hardship to the troops, particularly the British, as their commissary department was grossly incompetent. For months the men were clothed in rags--cold, hungry and short of everything. Often the supplies were frustratingly on ships docked in harbor. During this time, four times as many died from disease as did from enemy action. One regiment, nominally over a thousand men strong, was reduced to a total of seven men by January 1855.

In early September 1855, Sebastopol finally fell and the war drew quickly to a close, although hostilities still continued through February 1856.

The Peace of Paris on March 31, 1856 brought the war to a conclusion.

French, English and Romanian photographers all documented the war, although this usually amounted to photographs of posed groups of the soldiers, landscapes of campsites, pictures of battle sites after the actual battle, and images of the ships, docks and supplies, which were all snarled with poor planning and organization. In particular, it was James Robertson and his partner Felice Beato for the English and Colonel Jean-Charles Langlois and his assistant Léon Eugène Méhédin for the French who took the most "realistic" photography of the chaotic results of the battles themselves, although dead bodies are non-existent in any of the photographic coverage of the war. This was a war of propaganda from its earliest beginnings, not unlike today's wars, and, just as they are today, images of dead bodies were not meant for public consumption.

All the photographs of the Crimea are scarce in good condition, and most, except for Fenton and Robertson's images, are exceedingly rare.

In the first year of the war before it reached the Crimea, a Romanian-based photographer Carol de Szathmari (actually a Hungarian from Transylvania) decided to take his camera to the battlefield. Using a wagon specially equipped with a dark room for processing the glass plates with wet collodion, he traveled to the banks of the Danube and other sites of the war. In April 1854 his van became a target for the Turkish artillery from Oltenitza, who thought it belonged to a Russian spy. Szathmari was lucky that the gunners missed--a tribute to the Turkish army's shooting skills at the time.

Besides landscapes, fortifications and battlefields, he photographed various troops, both Turkish and Russian, and their commanding officers. He also photographed the "camp followers" who gave these officers succor. He exhibited an album of his photos at the Paris World Exposition of 1855. Most of Szathmari's prints from this period are salt prints.

Because Szathmari's were the first images of the war, taken prior to Roger Fenton's large collection of photographs of almost a year later, his album was much praised, and he was presented with many awards. He eventually offered his work to Queen Victoria, Emperors Napoleon III and Franz Josef I, and to other royalty of Europe.

The album's contents are known only from descriptions of the French reviewer, Ernest Lacan, in his brochure Esquisses photographiques a propos de l'Exposition Universelle et de la Guerre d'Orient (Paris 1856). Unfortunately, few of the albums have survived in any form: the one offered to the French Emperor burned in the Tuilleries Palace during the Commune of 1871; Queen Victoria's copy also burned in 1912 during a fire which ravaged Windsor Castle (although several images did survive); those in Austria and Germany disappeared during WWI and II; and the copies which might have been stored in the artist's studio vanished in 1944 when Bucharest was bombed and Szathmari's house, with all its treasured collection, was destroyed.

The British government made several official attempts to document the war through photography. In March of 1854 an amateur photographer, Gilbert Elliott, photographed views of the fortresses guarding Wingo Sound in the Baltic Sea from aboard the Hecla, the same ship that was to carry Roger Fenton to the Crimea 11 months later. Elliott's photographs, though praised for their clarity in contemporary accounts, apparently have not survived.

A more substantial effort to photograph the war, lasting from June to November 1854, came to a tragic end. Richard Nicklin, a civilian photographer, was lost at sea, along with his assistants, photographs, and equipment, when their ship sank during the hurricane that struck the harbor at Balaklava on November 14, 1854. Apparently a single album of his work surfaced in South Africa.

In the spring of 1855, at virtually the same time that Roger Fenton was in the Crimea, another government-sponsored attempt was made. Two military officers, ensigns Brandon and Dawson, were quickly trained by London photographer J.E. Mayall and then dispatched to the Crimea. Their photographs, which were apparently retained for a number of years in official military files, without any actual use or notice, have disappeared without a trace.

Larry Schaaf and Hans Kraus,Jr. have attributed three paper negatives of the Crimea to Charles Clifford in Sun Pictures, Catalogue Ten, nos.40-42, although no other photo historian has added anything to these claims. Clifford had made few paper negatives after the early 1850s. Certainly by the time of the Crimean War he was working only in collodion wet glass plate negatives, and it would have been highly unusual for him to switch back to an earlier format.

William Agnew, of the publishing firm Thomas Agnew & Sons, must have proposed Fenton as the photographer for a commercial publishing venture to the Crimea sometime immediately after Nicklin was lost at sea, for during the fall of that year Fenton purchased a former wine merchant's van and converted it to a mobile darkroom. He hired an assistant, and traveled the English countryside testing its suitability. In February 1855 Fenton set sail for the Crimea aboard the Hecla, traveling under royal patronage and with the assistance of the British government.

To get to the Crimea and to work there, Fenton needed the cooperation both of the war ministry and the actual commanders in the field. He got letters of introduction to all of them written by none other than Prince Albert, and was given transport in a government vessel for himself, his photographic assistant Marcus Sparling, a servant (called William), three horses and his photographic van with 36 large cases of equipment, including five cameras and over 700 glass plates.

Fenton used Sparling, a former corporal in the 4th Light Dragoons as his assistant while in the Crimea. Sparling was no stranger to photography, and, in fact, had already invented a magazine-type camera in 1850 that took 10 wooden frames. Fenton took several important portraits of Sparling, including one driving Fenton's photography van and one in Zouave costume. When Sparling returned from the Crimea, he continued to work as a commercial photographer until he died in 1860. Sparling wrote and had published the influential "Theory and Practice of the Photographic Art" in 1856.

While Fenton was in the Crimea he had plenty of opportunity to photograph the horrors of battle and wrote often about them to relatives in England. He had several friends and acquaintances, including his brother-in-law, Edmund Maynard, who became war casualties. But Fenton shied from images that would have portrayed the war in a negative light for a number of reasons, among them, the limitations of photographic techniques available at the time; inhospitable conditions (extreme heat during the spring and summer months that Fenton was in the Crimea); and political and commercial concerns (he had the support of the Royal family and the British government, and the backing of a publisher who hoped to sell sets of the photographs).

Roger Fenton's Crimean War photographs represent one of the earliest systematic attempts to document a war through the medium of photography. Fenton, who spent fewer than four months in the Crimea (March 8 to June 26, 1855), produced nearly 700 glass plate negatives under extremely trying conditions. While these photographs present a substantial documentary record of the participants and the landscape of the war, there are, as I have noted above, no actual combat scenes, nor are there even any scenes of the devastating effects of war. As a consequence of his time in the Crimea, Fenton broke several ribs, contracted cholera (some say it may actually have been malaria) and had to return home before his goal of photographing the fall of Sebastopol. A number of observers noted that this debilitating experience may have contributed to his early demise in 1869 at the very young age of 49.

On September 20th, 1855, an exhibit of 312 of the photographs opened at the Water Colour Society's Pall Mall East establishment in London. Sets of photographs went on sale in November. The Crimean War photographs were offered in a series of parts, in which a group of 160 images was described as the "Complete Work" or the "Entire Work" in the catalogue of the publisher Agnew. Apparently 337 different images were actually offered by Agnew on separate mounts, although reportedly 360 different images were shown to the Emperor Napoleon, and nearly 700 had been taken by Fenton, according to some sources. The prints were also sold in a series of titled volumes. Although the number of photographs per volume was fixed, it appears that it was up to the individual buyer to select the particular choice of subjects. The photographs sold singly were priced from half a guinea to a guinea.

Although the pictures were widely reviewed and advertised, when the war ended, interest in photographs of the war ended with it, and the entire stock of unsold prints and negatives were auctioned off by December of 1856.

One of the first photographers in the general area of the war was the Scotsman James Robertson, who was taking photographs of the preparation for war, the hospitals and supply lines in Scutari across the Bosporus Straits from the Crimea in 1854.

Robinson had worked as a designer and engraver at the Royal Mint in London in the 1830s. He was one of several employees who went to work at the Ottoman Mint in Constantinople, starting work there in 1840 as chief designer or engraver. At some time in the next decade he learnt photography and opened a studio in Pera, the European district of Constantinople, in the 1850s.

Around 1850, possibly in Malta, he met the Beato family, and Maria Matilde Beato became his wife. He probably taught her two brothers, Felice and Antoine (sometimes known as Antonio), how to take photographs. They later became his assistants and partners.

When Roger Fenton had to leave the Crimea in 1855, Robertson and his partner Felice Beato replaced him in Sebastopol, taking pictures of battlefields, the Balaklava harbor and the army over the next year. It was Robertson and Beato, not Fenton, who documented the actual fall of Sebastopol, the resulting devastation and the final battles that actually ended the war.

The Crimean War gave the pair an experience that would aid them in their documentation of the Indian Mutiny, the Opium War in China in 1860 and the Sudanese colonial wars in 1885 (the latter two only covered by Beato). In these later conflicts, gruesome dead bodies would litter the images--a photographic first not portrayed in the Crimean coverage. Robertson died in 1881.

On the French side several photographers joined the fray. A few months after Fenton had left the Crimea, Colonel Jean-Charles Langlois, a history painter who fought in the last Napoleonic campaigns, came on the scene together with a young photographer, Léon Eugène Méhédin, in order to make preparatory shots for his Panorama of Sebastopol, which was presented to the public from 1860 to 1865 in a rotunda built on the Rond Point des Champs Elysées by Gabriel Davioud. Langlois was rumored to have died in this same building in 1870. In 1830 Langlois's "Battle of Navarino", a most spectacular panorama, was perhaps one of the earliest examples of simulated or virtual reality to the extent that it was used as a training aid for naval cadets.

His 28-year-old photographic assistant, Mehedin was born in 1827 in Laigle and raised in Normandy, and studied architecture in Paris, where he also took up photography, possibly around 1850 as a student of Gustave Le Gray. He was sent officially to the Crimea as a photographer.

Although Méhédin continued his career as an architect (he designed a railroad station with an escalator for the city of Rome), he also conducted photographic expeditions into Nubia, Egypt, Italy (the military campaigns of 1859) and Mexico throughout the 1850s and 1860s. He died in 1905 in Blosseville-Bonsecours near Rouen.

Langlois's military and governmental connections made it relatively easy for him to get access to the Crimea in the late fall of 1855 (Nov. 13) through the following year and the end of the war, even though he had originally planned to stay a mere three weeks. One of his albums, which the photographs on this web site come from, was gifted to Monsieur Achille Fould, French Minister of State and the Imperial House, who, according to the Dictionnaire du Second Empire by Jean Tulard, was the next ranking official after the Emperor. He was a member of an influential Jewish banking family, becoming first Minister of State responsible for cultural affairs, then Minister of Finance in 1861 to his death in 1867. Another copy dedicated to Emperor Napoleon III is in the Bibliotheque Nationale. Still another album was given to Le Marechal Pelisser, chief of the French army of the Orient, and can be found in the Musee de l'Armee, Paris. These gifts show the kind of connections that Langlois had made.

Langlois and Méhédin both used paper negatives rather than the faster wet collodion glass plates that the English and Romanian photographers mainly used.

In a series of 56 letters to his wife, Langlois reported the extreme difficulties with his life in the Crimea and with the practice of photography itself. He noted that in the dwindling light of late fall and early winter many of his paper negatives required many hours (as much as four) of exposure. He also noted the difficulties in preventing the covering up of all traces of destruction by the military before he could make his photographs.

In addition, Langlois complained to his wife about Mehedin's "abrupt nature" and his duplicity. Mehedin's old teacher Gustave Le Gray tried to get him to take photographs of the Crimea for his studio. Langlois blocked this effort. Apparently Langlois and Mehedin received most of their supplies from Le Gray's Paris company, and Langlois complained to his wife about the poor quality of some of the supplies, particularly the collodion. His wife went to the Le Gray studio and got Le Gray's personal attention over the matter.

In addition to Méhédin's help, Langlois may have learned about photography through a chance meeting with photographer Maxime Du Camp in Karnak, Egypt, where Langlois was drawing at the time. At the very least, his discussions with Du Camp must have intrigued him to learn more about this new medium.

Frederick von Martens, a well-known Paris-based photographer and publisher, probably printed the photographs in the albums because his blindstamp is on the mounts, although the dilute albumen photographs are individually signed and titled in ink by either Langlois or Méhédin as well.

Another French painter/photographer team was noted Parisian marine artist-explorer Jean-Baptiste-Henri Durand-Brager (1814-1879) and his nearly anonymous partner Lassimone, who also photographed the war in 1855, although so much of their effort predictably focused on the French navy and the port of Kamiesch and the naval base at Sebastopol. As a French naval officer, Durand-Brager had led various explorations during his career, including a voyage to Senegal on which he was shipwrecked. He studied painting as a student of d'Isabey.

Authors Michele Chomette and Pierre-Marc Richard postulate that the other great French photographer-explorer Paul Miot may have learned about photography from the two when he was on board the Uranie or Laplace in the Crimea, from October 1855 to March 1856.

Lassimonne may have been a Parisian photographer, who exhibited at the 1857 Societe Francaise de Photographie's salon. A photographer with the same last name also worked earlier in Limoge as a daguerreotypist and miniaturist in the early 1850s.

E. Gambart & Co. of London and Bisson Freres of Paris were the pair's joint publishers; however, the work is so incredibly rare that it is doubtful that many prints or albums were ever produced. Much of the work is faded or in poor condition, because the prints made from the pair's collodion glass plate negatives were salt prints poorly fixed and/or washed. Twenty-four prints from the series were exhibited at the 1856 Manchester Photographic Society's Exhibition of Photographs at the Mechanics' Institute.

As a follow-up to the end of the war, Queen Victoria commissioned an album entitled "Crimean Heroes", by Robert Howlett and Joseph Cundall. The project was assigned as the troops returned from the Crimea to Woolich, England, yet most of the photographs were taken in Aldershot. Howlett and Cundall set up a temporary studio at Aldershot Camp during June and July 1856, as the troops congregated there before a grand London parade. The album focuses on the British soldier whose intense suffering changed a nation's thinking. These unsung heroes etched the Crimean War into British history with a brutal example of the futility of war, and a show of human endurance against all the odds. Several of the individuals shown in the image by Howlett & Cundall on the web site have recently been featured on a series of stamps focused on the Crimean War. If other English Crimean War images are scarce, Cundall and Howlett's photographs are very rare.

Other photographers, such as Maull & Polyblank tried to cash in by photographing some of the heroes and leaders of the war, including the image of Major General William Fenwick Williams that is in this Special Exhibit.

A true hero, Williams was British commissioner with the Turkish army in Anatolia during the war, and, having been made a ferik (lieutenant-general) and a pasha, he, in effect, commanded the Turks during the heroic defense of Kars, turning back several Russian attacks. He badly defeated the Russian general Muraviev in the battle of Kars on September 29, 1855. However frigid temperatures, cholera, famine, dwindling supplies and no hope of outside help compelled Williams to surrender on November 28.

For his efforts he was given a pension for life, a baronetcy, the grand cross of the Legion of Honor, and many other tributes. He was promoted from Colonel to Major General upon his return from Russian captivity. He later became a full general and commanded the Canadian armed forces, and was made governor of Nova Scotia and later Gibraltar.

On the French side, Le Gray was court photographer for Napoleon III and was commissioned to document the peacetime maneuvers organized by the Emperor in the summer of 1857 following the French involvement in the Crimean War.

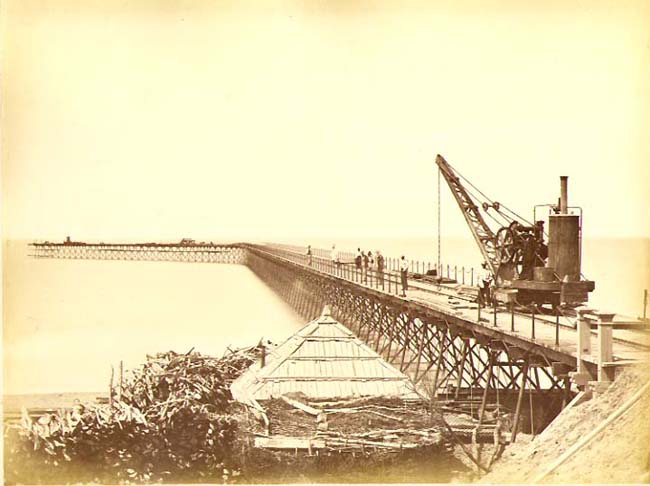

After the war, reconstruction efforts were also documented, but without much public attention. One such photograph is the last image in the exhibit, made about 1860 of Mr. Baly's Pier at Poti Caucasus in the Crimea.

Exhibited and Sold By

Contemporary Works / Vintage Works, Ltd.

258 Inverness Circle

Chalfont, Pennsylvania 18914 USA

Contact Alex Novak and Marthe Smith

Email info@vintageworks.net

Phone +1-215-518-6962

Call for an Appointment

Share This