Stanko Abadzic (Photo by Valerija Dujmovic).

In the last three decades, the Croatian photographer Stanko Abadzic has made his mark in the international photography world, including the United States. There has been a stream of exhibitions, in Paris, Prague, Houston, Istanbul, Vienna, Belgrade, Zagreb and other cities, and by now, he has published altogether 23 books. But it took a lot of hard work for him to get there.

Stanko Abadzic was born in 1952 in Vukovar, then part of Yugoslavia, a dictatorship headed by Marshal Tito. Vukovar became infamous during the Yugoslav Wars in 1991, when it saw the fiercest and most protracted battle in Europe since the Second World War. Stanko Abadzic and his family managed to get out alive, but spent years as refugees in Germany before settling in Prague in 1995. "I finally felt free, and it was in Prague that I was able to establish a career as a fine art photographer," he tells me when I call him in Zagreb, the capital of Croatia.

Going through his books is to enter a world in black and white. It's a world of subtlety and imagination, of interplay between people and buildings, of shadows and shapes, and, I think, a world of compassion and humanity. Stanko claims that he does not have a message, but nevertheless I think there is one--of spirituality and empathy. And in many images, I also sense a need to connect the present day with a world of a bygone age, whether it's the image of an old man with a bicycle in a dark alley in Prague or the shadowy figure passing the old houses with its crumbling facades, with lines of washing hanging high above in the Croatian coastal town Rovinj.

Stanko Abadzic, Nude No 13, Prvic Luka, 2020.

Nudes form another chapter in Stanko Abadzic's story. In some he explores the form of the human body, in others, the body and the location create a momentary architecture, captured in photography, while others are moments of shared intimacy with the model.

There are many echoes of the history of photography in his images, including photographs by masters like Henri Cartier-Bresson and André Kertész among others, but he uses these influences to create something of his own, above all, infusing the images with warmth and affirmations of life.

Stanko Abadzic resides in Zagreb, the Croatian capital. I started out by asking him about his early years and when and how he first became interested in photography.

"I grew up in Vukovar, which was a nice place to live back then. When I was 15, my father gave me a Smena 8 camera for my birthday. It was a Russian camera, pretty basic but I still have it and it's a cherished possession, as I took my very first photographs with that camera. Then a couple of years later, I joined a local photo club called Borovo, and I presented my very first exhibition at the club. That was when my interest in photography deepened. Taking pictures and working in the darkroom, it was all magical to me."

Were there particular photographers that you admired?

"Yes, there was Willy Ronis, Henri Cartier-Bresson and the other Magnum photographers, but I also liked the Chinese photographer Fan Ho very much. To me, they all represented the golden age of photography, and I fell deeply in love it. I also admired the cinematography in old films."

Did you study photography at college or university level?

"No, I studied German language and literature at university. As far as photography is concerned, I'm completely self-taught."

You grew up in Tito's Yugoslavia. What was it like? Did you feel restricted or that the eyes of the authorities were on you?

Stanko Abadzic, Fork and Eye Sign, 2025.

"For me, everything was okay. Life was actually very, very good. After my graduation, I worked as a manager at a big factory with 20,000 employees. It produced a wide range of products, from tires to shoes for Nike for the American market. In my free time, I took photographs. This led to a job as a photographer and correspondent for the newspaper Vjesnik. It was a great job and for the first time I was able to travel abroad. I made reportage in Tunisia, Malta, Turkey, Tunisia and Morocco. It was a very important time for me--both as a human being and as a photographer--discovering different people and different cultures. In Tunisia I connected with the Berbers, and they allowed me to photograph them in the dwellings they had built underground, a privilege not granted to very many. It felt truly special."

I don't recall ever having seen those early images. How come you haven't released them to the galleries you work with?

"There is a reason for it. I don't have the negatives. Following the collapse of Yugoslavia and the eruption of the civil war, Vukovar was the first battle zone in Croatia. Our house was completely destroyed and I lost 3,000 negatives. It was a terrible time. The situation was also very confused, not least as to what the final aims of it all were. I decided I didn't want any part of it, didn't want to take up arms, so I took my family to Germany, where we became refugees."

What was the situation like for you and your family in Germany? Did you work as a photographer?

"No, I took various jobs, anything I could get. There was no time to even think about taking photographs, just work and sleep. I worked at a pizza place, then at a transport company, anything just to survive. Our lives as refugees were not easy. There was constant uncertainty. Every three months, we had to go to a police station to extend our "Duldung", that is, permission to stay in Germany as refugees. And we never knew if we were going to get an extension or be ordered out of the country from one day to the next. After five years, the authorities would, according to the law, have to grant us permanent permission to stay. In 1995, after four years, they ordered us and many other Croatian refugees to leave. There was nothing left in Vukovar for me and my family to return to. The town was completely destroyed and with it our house. Rules were very strict in Germany and we had to inform the authorities in Germany exactly where we were going and by which border crossing. We decided to go to Prague. And it was a wise decision because it changed everything."

Stanko Abadzic, the Refuge, Prague, 2002.

Once in Prague, how did life change for you?

"I felt a change immediately on the first day we arrived, "This is the right place for me!" It was August and the sun was shining. In Prague, I could finally live again. It was like being reborn. I got permanent permission to stay and I just felt so free. The city was beautiful; it had wonderful architecture, and there was such a great atmosphere. It was all very inspiring to me, and I began to take photographs again. There were photography galleries in Prague. There was a faculty for photography and film, and it was a great place to be a photographer. I also discovered all the important Czech photographers: Josef Sudek, Jaromir Funke, František Drtikol and many others, who would influence me in different ways."

Did you start working as a photographer in Prague?

"No, initially I took a job as a teacher in a state school, teaching German. One day, while the students were given a written test, I was standing by the window, looking out. In the park below, among the trees and the flowers, I saw a couple who were kissing. It was a magical moment for me. In a flash, I realized that my real life was not to teach in a school, that I should be out there, taking photographs. I went straight from the classroom to the secretariat and handed in my notice, informing them that I would stay for another month, until the end of term, but that they would have to get another German teacher."

Stanko Abadzic, In the Old Yard, Prague, 2000.

What did you do next?

"Just one week after I handed in my notice at the school, I got a job at a company called Super Poster. They had approximately 20 huge billboards at various locations in Prague. The job consisted of documenting the billboards during the night and also the day. The company would then send the documentation to their clients. I finished the job in three days and three nights, and I earned as much as I had done working one month as a teacher. This job gave me a lot of free time to do personal work. I would walk around the city and come home absolutely exhausted, but at the same time, very, very happy. I was doing what I loved. Prague was, and is, such an interesting city. I would go into old courtyards, wander down cobble-stoned alleys and streets. In Germany, everything was stressed and rushed. In Prague, there was no hurry. In discovering Prague, I also discovered myself as a fine art photographer. Every day, I seemed to reach deeper and deeper into the medium."

There's a great sense of calm in the images of Prague.

"I think the images were my way of dealing with what had happened, the atrocities in my home town of Vukovar, the horrors of war, my experiences as a refugee. I managed to achieve an emotional balance through my photography."

Was it in Prague that you presented your first exhibition as a fine art photographer?

"Yes, and the very first one was called "In the Mirror of Life". I also produced my very first book, with the same title. The first print run was 400 copies and I sold them at Galerie Dom Josefa SUDKA, in English, the Josef Sudek Gallery. The book sold out very quickly, as all year, there were many German tourists in Prague, all wanting a memento of the city. I decided to print another 1000 copies. They sold out within a year. For every book, I made 10 German marks and I realized that by producing books, I could make a living as a fine art photographer."

When did you start selling prints? Was that in Prague?

Stanko Abadzic, Untitled (Man Repairing Bicycle Tire), 2000.

"Yes, it was in Prague. My first big sale came about in quite a strange way. A friend of mine called me and said, "Stanko, I didn't know that you exhibited your work in fast food restaurants!" I thought she was joking! But no, she was serious and gave me the address of the restaurant. I went there and was surprised to see 40 of my images, framed and hung on the walls. Looking closer, I discovered that the images had been cut from my book In the Mirror of Life. I asked to see the owner and gave him two options, buy original prints from me or deal with my lawyer. He decided to buy originals. I charged him 5,000 German marks, big money for me at that time, and it enabled me to buy a Pentax 645 camera, and it's the camera I still use to this day."

How did you start selling your prints internationally?

"In 2002, I got divorced and moved back to Croatia, initially to an island called Krk, and after three years I settled in Zagreb. Anyway, in 2002, I was surfing the internet and came across the site of Alex Novak's Contemporary Works/Vintage Works. I really liked what he had on his site, a lot of truly great, classic photography. I decided to give him a call, just to see if he would be interested in representing me. We had a great conversation and he told me, "Stanko, I have two photographs by you!" I was surprised because he hadn't bought them from me. It turned out he had bought them from my gallerist in Prague, Jiri Jaskmanicky. Alex introduced me to the American market. He bought 16 prints straight away and was glad to represent me. We have been working together for over 20 years now. I also work with Catherine Couturier in Houston and in October this year, she showed an exhibition of my nudes. Alex and Catherine have been very important for me. 95% of my income from print sales comes from the United States."

Stanko Abadzic, In Front of the Mirror, 2000 (Sold out in smaller size, but available in 37-1/2 x 27-5/8 in. silver gelatin prints only from Contemporary Works/Vintage Works).

Let's turn to the subject of nudes. Your approach to them is quite unusual in that you always work with the same model.

"Well, in the very beginning, I didn't. I started doing nudes in Prague. The very first one was of a model in front of the mirror and the image ended up winning an award at Czech Press Photo. Initially, I hired different models, and those images are in my first book of nudes. But with hired models, things were always rushed, not enough time to explore different ideas so I decided to work just with one model. The collaboration has resulted in four books with this one model and several exhibitions. Working with one model means constantly coming up with new ideas, keeping it fresh, whether it's finding interesting locations, using different lighting or changing hair styles, but we always come up with something new."

How does that collaboration work? Do you discuss locations, poses, etc.?

"Yes, we do and that's important for the process. She is a big inspiration to me. We have discussions, sometimes she suggests poses, and she is very sensitive to the ambience of the places where we shoot. It all comes down to trust. I promised her not to make nudes with other women, and she promised me not to pose for other photographers."

Stanko Abadzic, Female Nude Holding Ball, 2024.

It seems to me that you choose locations very, very carefully.

"For me, locations are 50% of a successful photograph, whether work in Spain, Greece, Italy or here in Zagreb. A location has to have something, whether it's a sense of mystery or a certain atmosphere."

You have often stated, "I have no message. I don't question anything. I'm just creating photos." But I don't think it's possible to just create photos. To me, there is a kind of message in your images: "Pay attention to all those little moments in life. Don't let them slip by."

"I have made that statement for a reason because here in Croatia, curators always ask, "What's the message?" It's just such a stupid question! Photography is a visual medium. You can't really question anything with it. It has its own language. Roland Barthes talked about the punctum and the detail in a photograph that takes you on a journey to discover things about a photograph."

I also interpret many of your photographs as a kind of love letter to Europe, to perhaps a Europe of a bygone age.

"I'm European, and I like Europe because it has a very big and very rich culture, be it architecture, painting, sculpture, photography, literature or music. There is much to be inspired by. I guess I have always been influenced by mainly European photographers. When I grew up, it was not so easy to get American photography magazines. It was much easier to get French or German magazines, showing European photography, and that has stayed with me. The sad thing is that cities in Europe are becoming more and more uniform. Modern buildings look alike everywhere you go: steel and glass. It's all to do with globalization. With old architecture, you can tell from the architecture what city you're in."

Stanko Abadzic, Curiosity, Prague 2002.

There are elements of modernism, sometimes surrealism in your images and influences from the French humanist photographers.

"It's probably the French humanist photographers who have influenced me the most. Yes, sometimes there's surrealism but I don't think about styles or schools when I make images. It's about what I see and feel at that particular moment."

Silhouettes and shadows are recurring elements in your images and you use them to extraordinary effect.

"Light and shadows are the very essence of black and white photography. It is the heart of it and wonderful to work with. And nobody can escape his or her own shadow. I see shadows as beautiful ornaments in photographs, and how they work and change depends on how you change your viewpoint and position."

Another reoccurring theme is bicycles. Why do they fascinate you so much?

"It goes back to my childhood. After the Second World War, my father was chief of police in Vukovar and he was given a bicycle to use as transport. He left the job but decided to keep the bicycle. My brothers and I weren't allowed to use it. Even so, we did when he was not at home. For me, a bicycle represents a slower pace of life, I would say, how life should be lived."

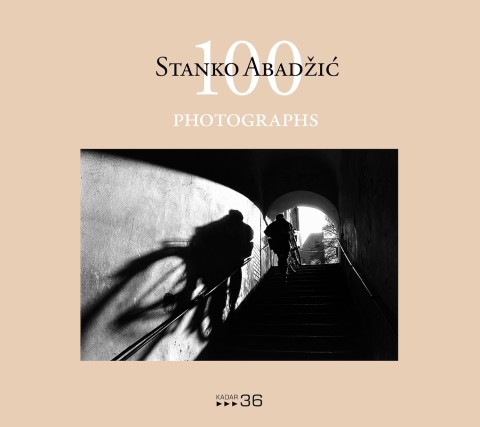

Stanko Abadzic's latest book is called, "Stanko Abadzic: 100 Photographs", and is available from Contemporary Works/Vintage Works.

Earlier this year, you published your 23rd book: 100 Photographs by Stanko Abadzic.

"It's a selection of my best 100 photographs from the last 20 years. It was quite a difficult book to put together because I have taken photographs in so many places, Europe, Morocco and Uzbekistan. I could easily have produced two books with 100 photographs in each. It's published by Kadar 36, an association of photographers, based in Zagreb."

You have produced many city books over the years, including Odessa, Lisbon, Budapest, Zagreb, Istanbul, Prague and Paris. The images in the latter, Paris – Sketches for a portrait of the city show the city in an unexpected way.

"It was a very difficult project. Paris is known as "The City of Light", with lovers on every corner as the cliché goes! Well, I went there in January and February, when there was no light, just gray skies, and very few tourists. The trees were bare. So, no light and no shadows, which is what my photography is about. I had to come up with a different approach so I went to the outskirts of the city, photographed areas, streets and buildings that are rarely seen in photographs. In the end, I was happy with the results and published a selection of the images as a book. Some of those images took a lot of work to get. I found one location, with a fence, and I then had to wait for three days to capture the scene when the conditions were just right. I ended up with a very different kind of book on Paris. Which was good because I was also mindful of how Paris had been photographed before by Willy Ronis, Henri Cartier-Bresson and others, and I didn't want to repeat what they had done."

Stanko Abadzic, Trees and Snow (from the Paris Cycle).

Even in the other books of images of cities I have visited, I'm struck by locations I'm not familiar with.

"Getting images that are really special is about spending time, paying attention to where you are, discovering secrets on your own, unravelling mysteries. This takes patience, of course, and not everyone has patience these days. When I work, it's almost like sinking into a meditative state. Being at one with the scene."

You mentioned your Pentax 645 camera earlier.

"That's my main camera. These days, when I'm out taking photographs, I also bring a digital camera. I use the digital camera first. If it results in a great image, I shoot it on film."

You work in black and white. Have you ever considered working in color?

"No, black and white photography is my medium, how I express myself. That's not to say that I don't appreciate color photography. I like the work of the French photographer Bruno Barbey. His colors are just so beautiful, almost like aquarelle, not aggressive, very soft. But I'm sticking to black and white."

You mentioned the association of photographers Kadar 36 before. What's the photography scene in Croatia like in terms of galleries?

"There are galleries that show photography, but they are not specialized photography galleries but mainly painting galleries. Unlike the Czech Republic and Hungary, there is no museum of photography in Croatia. Photography isn't really accepted as an art form here. In fact, I know of only two people who collect photography in a serious way in Croatia. It's a shame because there are some really great photographers in this country."

Can you see that situation changing?

"I think there would have to be a proper museum of photography, one that put on permanent exhibitions of Croatian photography, temporary exhibitions with new photographers, and for that museum to connect with museums and galleries around the world."

You have been incredibly productive over the years. Have you started working on a new book yet?

"I plan to publish my next book in two years. It will be a book of my best 100 nudes but as I found with my latest book, I could easily make two books!"

To see and to order photographs by Stanko Abadzic, go here: https://iphotocentral.com/common/result.php/38/1000/10000/BBB/Stanko+Abadzic/0/0/8.

To order one of his currently available photobooks, go here: https://iphotocentral.com/common/result.php/36/KKK/Stanko+Abadzic/0.

Michael Diemar is editor-in-chief of The Classic, a print and digital magazine about classic photography. In August 2025, he cofounded Vintage Photo Fairs Europe, an organization focused on promoting independent tabletop fairs in Europe and spreading knowledge about classic photography in general. He is a long-time writer about the photography scene, writing extensively for several Scandinavian photography publications, as well as for the E-Photo Newsletter and I Photo Central.

Share This